![A Museum is Visited While Another One is Imagined [2018]](http://moanamayall.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/hp-40-b.jpg)

A Museum is Visited While Another One is Imagined [2018]

Video, 18’08” PT with English subtitles.

Argument, Camera and Edition: Moana Mayall

With Thainã de Medeiros and Moana Mayall (interviewer)

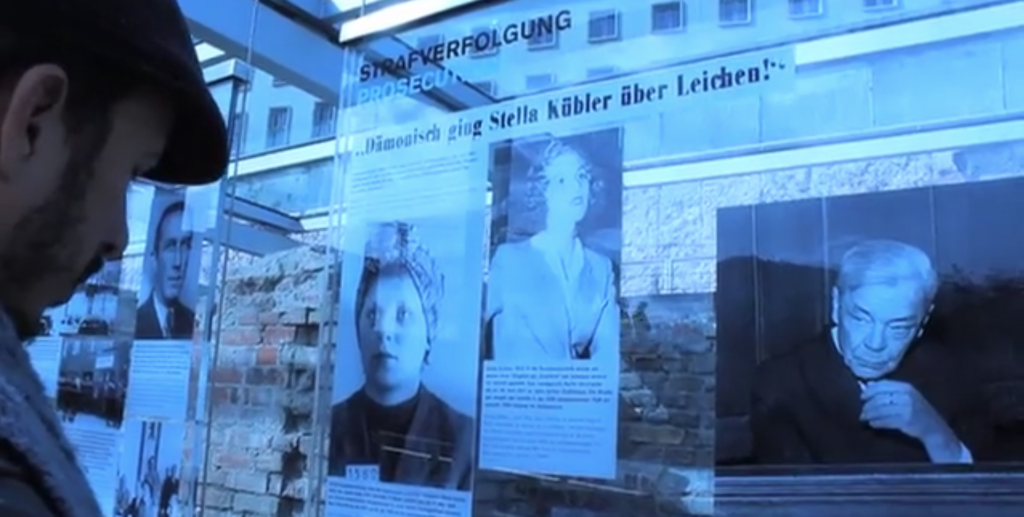

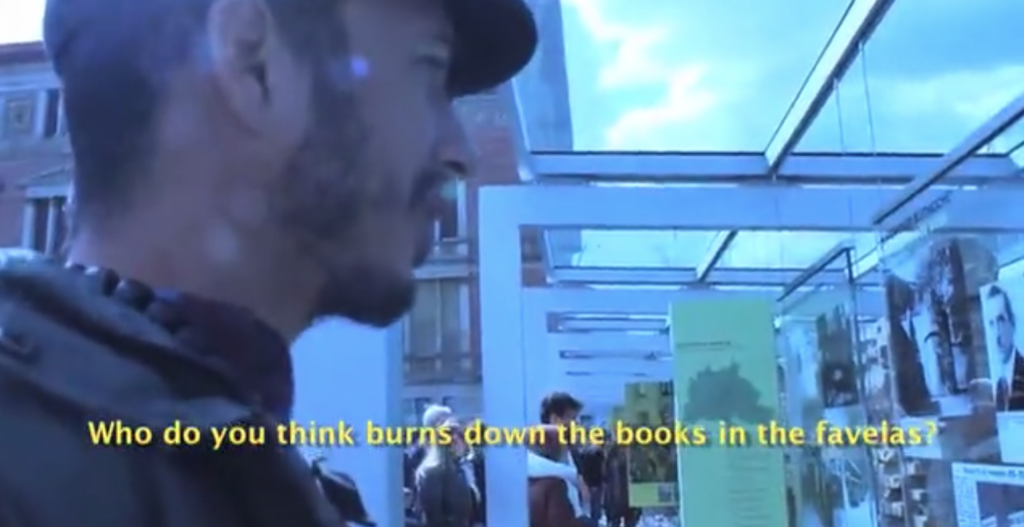

History, as commodity, is revealed in its own battlefield for the final,“official” words, books, and also museums, tourism industry and so on. What remains is likely to be fiction, unless we decide to listen through the apparent noise of the many voices still unheard. This video was recorded in April, 2016, in Berlin, with Thainã de Medeiros, media activist of Papo Reto (Straight Talk) collective, Complexo do Alemão favela, and also a museologist. The Museum Topography of Terror narrates, with a lot of audio / visual documentation, the rise and fall of the Nazi regime of the Third Reich in Germany, and is located in the ruins of one of the former SS and Gestapo general headquarters, and to the remains of the Berlin Wall. How would a museum (about the war) in the favela be like, maybe one day in the ruins of the UPPs (Pacification Police Units)?

At the time the video was recorded, Brazil was going through the coup against President Dilma Roussef, Rio de Janeiro was getting ready for the Olympic games, the favelas suffered more peaks of military repression, and students occupied several public schools in demonstrations all over the country, reinventing and teaching resistance to generations cushioned by the alienating trauma of the military dictatorship.

The documentation of the meeting and the conversation in critical space is part of artistic research project A Portal Experiment (Alemão/Alemanha), in collaboration with Papo Reto collective. This video is released on the internet some weeks before the elections of 2018, as part of the campaign #BerlinAgainstFascism, focused on awareness and resistances against the threat to human rights and democratic institutions in the country, with the election of Jair Bolsonaro.

See the video in Portuguese, with English subtitles. / Ver o vídeo em português, com legendas em português.

In Manifesto DEMOCRACY IN BRAZIL UNDER THREAT (October, 2018):

“Bolsonaro’s hard-line conservatism constitutes a serious step backward for Brazilian society and a threat to Latin America as a whole. With a idespread and unapologetic discourse of hatred that is littered with calls to wind back civil and social rights, Bolsonaro brazenly preaches discrimination against groups such as people of colour, women, LGBT people, and indigenous peoples, and defends the escalation of urban violence that has occurred throughout the entire presidential campaign. The candidate opposes gender equality, sexual diversity, the protection of the environment, freedom of movement and association, activism, public education and scientific research, workers’ rights and social programmes. Furthermore, he presents himself as the candidate who will fight corruption, when the military dictatorship, which he praises, was an extremely corrupt regime.

By basing his campaign on a misinformation war and using military marketing tactics full of hate speech and fake news, Bolsonaro has led a fractured population desperate for solutions to severe political and economic crisis to believe that he is a new and viable option. But he in fact represents traditional establishment politics, having spent 27 years on the backbench in Congress after a military career from 1977 to 1988, during which time he consistently propounded far-right views opposed to democratic principles. More recently he has cynically exploited the electoral machine to help his three sons get into office: they are now members of the Senate and the Federal and Municipal Chambers respectively.

Bolsonaro’s party defends authoritarian measures and a flagrantly bigoted idea of government, which can bring irreversible losses to the Brazilian population and the nation’s globally invaluable biodiversity. Bolsonaro’s policies include, but are not limited to, the following:

1: Labor reforms based on the creation of a new work and social security card, which will make individual contracts even more precarious, and the wholesale abolition of a number of basic work rights, such as mandatory collective bargaining and the thirteenth month of pay, which date back to the 1950s.

2: The strategic privatization and/or dissolution of at least 50 of the country’s 150 state-owned companies.

3: The subsumption of the Ministry of Culture (MinC) into the Ministry of Education (MEC), which would result in further cuts to and a loss of autonomy in the cultural sphere.

4: The creation of military schools in every major city in the country. Bolsonaro defends distance education from elementary school onward, and claims that schoolchildren should be taught that the brutal Brazilian dictatorship that reigned from 1964 to 1985 was a democractic movement.

5: The reduction of the country’s current 25 ministries to 15, with the Ministry of the Environment to become part of the Ministry of Agriculture. The latter is responsible for watering down the regulation of pesticides, which has already lead to Brazil being the most pesticide-soaked country in the world, and for stripping current regulatory bodies IBAMA and ANVISA of the resources needed to assess a project’s impacts on the environment and human health.

6: In his first speech after the confirmation of the second round, Jair Bolsonaro promised to “put an end to all activism”, a clear and direct threat to social movements.

7: The complete disregard for existing, legally-recognized indigenous land boundaries, and the outright refusal to process existing indigenous and quilombola land claims, which the Brazilian State is expressly obliged to do according to the 1988 democratic constitution. This leaves indigenous peoples’ lands a way of life exposed to the genocidal threat of monoculture plantations, intensive animal farming, and mining.

The second-round vote will be held on October 28th: there are only ten days left to support Brazilian society and to raise the international alarm about the rise of extreme right-wing thought and violent practices in the country, and about the profound risk of having Bolsonaro as president. All institutions, parties, organizations and movements committed to democracy as the best means of dealing with political differences, must fight to banish autocratic and violent discourses and policies that dubiously present themselves as panaceas to social and economic crises. We must learn from history and do everything we can to avert the dire consequences of going down this fascistic path. We, the undersigned, attest that Bolsonaro’s election would unequivocally put Brazil, Latin America and the world at risk.

*A Portal Experiment

Complexo do Alemão <->Deutscher Komplex

This is a collective project that happens in constant collaboration, friendship and solidarity with collective Papo Reto , residents of Alemão and other favela communities in Rio.

Among hundreds of favelas in Rio, one was called Morro do Alemão (=“German’s hill”), actually named after a Polish man, Leonard Kaczmarkiewicz- who moved to Rio after World War I. He bought the land in the Northern Zone of Rio de Janeiro, at the time the first industries were being installed on Avenida Brasil, and became a faveleiro (=land owners who used to rent the ground to the favelados, in this case poor workers coming from Rio and other regions of Brazil, namely the Northeastern, also to work in these industries). It was not long before the place became known as Morro do Alemão (German’s Hill), due to Kaczmarkiewicz’s physical looks (a person of stereotypical European complexion is informally called “alemão”, “galego” or “russo”, in Brazilian Portuguese). Nowadays, the biggest complex of favelas in Rio, formed by the 16 neighbor favelas around Morro do Alemão, is known as Complexo do Alemão (German Complex).

Alemão (German), due to the inflated imaginary of World War II in all media, became a war code among drug dealing factions and nowadays it’s still a very popular slang in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, which means: 1. outsider; 2. enemy; 3. the police

A Portal Experiment consists of an ongoing interdisciplinary cartography* shared with the public in the form of collaborative actions and mixed media artworks/ exhibitions/ archives, where feedbacks in-between both territories are also taken into account for the next editions. It takes place in-between two remote territories: one is Complexo do Alemão (=“complex of the german guy”/ “german complex”), a group of 16 favela communities located in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and the other is Berlin, Germany.

The cartography* is formed by opening some “portals” in-between the official maps, which gives me access to different layers of history and (psycho)geography: traces, gaps, records, memories, affections, synchronicities … Usually two places, themes or situations are chosen-one in Complexo do Alemão and the other in Berlin. Some autobiographical nodes are also highlighted in the portal cartography: my own personal stories “excavate” the “his-tory of the world”, as well as the somewhat “silent” stories of my country, histories yet to be told by our own people.. . in each approach, the “excavation” continues, a great deal influenced by personal experiences and random (interdisciplinary? non- disciplined?) linkings. The many layers overlap in different crossings, resisting the limits of the official territories and narratives. Beyond the juxtaposition of fragments from both diverse worlds, the idea of the portal also provokes the perception of continuity between historical processes in Brazil and Germany.

In the favela, my “German complex” is my “white middle-class complex” . I’m an outsider, in-betweener, set apart from the favela, in an apartment in the southern Zone of Rio.

Initially sponsored by Dom Pedro II (end of XIX century), the colonization of Brazil by Germans and Italians not only had the objective of populating uninhabited regions of Brazil, but was also a eugenicist project for the creation of a genetically and culturally whiter middle class.

An important, practical and ethical dimension of this long term project- so far independent from institutional funding- is the ongoing exercise of listening and horizontal collaboration with favela social movements in Brazil. Since 2013, the project is in collaboration with the media activism collective Papo Reto (formerly members of Ocupa Alemão), a network of activists reporting issues that are relevant to Complexo do Alemão and other favela communities, engaging in copwatch and counter stereotypes, while also fostering spaces for dialogue and exchange.

What is it like to talk about a so called “other”, in a context where I am also considered an “other” myself ? While my social status of “white middle class” in Brazil entails a more privileged condition in terms of Brazilian society, in Europe it’s my South American “mestiza” background that will connect me to Afrobrazilian and Indigenous references, not refusing the problematics and critical, colonial, reflections both categories may bring about. The way I inhabit Alemão, being now in Berlin, as an outsider in both places, leads me to some other kind of “territory”, yet to be explored as both places relate and talk to each other, as they recombine or remix in voice, image, imagination, history and fiction: “synchroni-cities” in progress…

Ich bin nicht typisch/ Ich bin nicht so Brasilianisch in Brasilien./ Vielleicht eine echte Brasilianerin bin ich hier, in Deutschland./ Eigentlich, bin ich eine “Alemã” (Deutsche) in der Favela.” [I’m not typical/ I’m not so Brazilian in Brazil./ Maybe I am a real Brazilian here, in Germany./Actually, in the favela, I am an “Alemã” (German)

The portal is the opposite of the wall. Through the poetic strategies of collage/remix/ text cut ups, “decolonial décollage”, streams of consciousness, multidirectional memory** and psychogeographic drifts, this project intends to activate a dialogue environment between the two territories- yet generating a new hybrid territory which remixes intimate and geopolitical landscapes. I work with very diverse media, depending on how the contents inspire me- the experimentation with formats and methodologies is also part of the process.

Notes

* by “interdisciplinary cartography” I mean alternative ways of mapping, expanding the meaning of territories through their living realities, dialogues and the research references of the project. The methodology consists of bridging different fields of knowledge, namely history, visual arts, poetry, sound arts, as well as an ongoing personal archive of experiences.

“The practice of a cartographer refers to, fundamentally, the strategies of the formations of desire in the social field. And little does it matter which sectors of the social life he/she chooses as an object. What matters is that he/she remains alert to the strategies of desire in any phenomenon of the human existence that one sets out to explore: from social movements, formalized or not, the mutations of collective sensitivity, violence, delinquency. . . up to unconscious ghosts and the clinical profiles of individuals, groups and masses, whether institutionalized or not.

Similarly, little matters the theoretical references of the cartographer. What matters is that, for him/her, theory is always cartography-and, thus being, it creates itself jointly with the landscapes whose formation he/she accompanies (including, naturally, the theory introduced here). For that, the cartographer absorbs matters from any source. He/she has no racism whatsoever regarding frequency, language or style. All that may provide a language to the movements of desire, all that may serve to coin matter of expression and create sense, is welcomed by him/her. All entries are good, as long as the exits are multiple. ”

in Sentimental Cartography, Suely Rolnik

** Michael Rothberg proposes the concept of multidirectional memory from concluding that the assumption of a competition or comparison between different victim histories is analytically unprofitable. “Against the framework that understands collective memory as competitive memory – as a zero-sum struggle over scarce resources – I suggest that we consider memory as multidirectional: as subject to ongoing negotiation, cross-referencing, and borrowing; as productive and not private.”. (Rothberg 2009:3 in Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (Cultural Memory in the Present). He proposes to observe the worldwide memory of the Holocaust as not diminishing the importance of other victim stories, but rather as able to produce articulation. In doing so, the reference to other stories may function beyond their temporal and spatial location, contributing to the collective recognition of suffering.